Scotty “Pick Six” McKeever and I drove at illegal speed along a wide Florida highway in his black pick-up truck, talking about horses. We were running late. We’d gotten lost on our way to the racetrack, which was odd, given that the entrance is marked by a 110ft-tall statue of Pegasus fighting a dragon. On special occasions, it breathes fire. We arrived at Gulfstream Park, a sprawling compound in the shadow of downtown Miami, just in time for the first race.

Inside, McKeever and I frequently stopped to let sleek thoroughbreds, followed closely by the human entourage tending to them, pass. We wound past gamblers, in various states of anticipation, and the tellers who take their bets. We took an elevator and a long hallway to an empty luxury suite overlooking the track, an enormous oval of grass and dirt, with a shimmering pond in the centre.

McKeever took a seat and hurriedly pulled a laptop from his bag. He booted it up and the algorithms within flickered to life. They displayed a colourful array of metrics and diagrams, rating each horse’s pace, genealogy, experience and probability of winning the race. McKeever fiddled with some virtual knobs, digested the output and, after a few minutes, logged into a livestream to tout his computer’s pick to the world.

The horses worked into the starting gate at the other end of the field, and a bell rang from across the mile-long track. Dozens of hooves slammed the dirt in syncopated rhythm, quiet at first, then louder, until they sounded like an approaching cavalry. The rolling thunder passed beneath us, and the dust settled. McKeever’s horse had won.

It was otherwise quiet on that September Friday at Gulfstream. From the suite’s balcony, I could see a dozen racegoers milling about on the track apron. They sipped beers, smoked cigars and watched the majestic animals walk back to the paddock. They waited around for another equine battalion to emerge for the next race. The patrons repeated this cycle all day, placing bets in between.

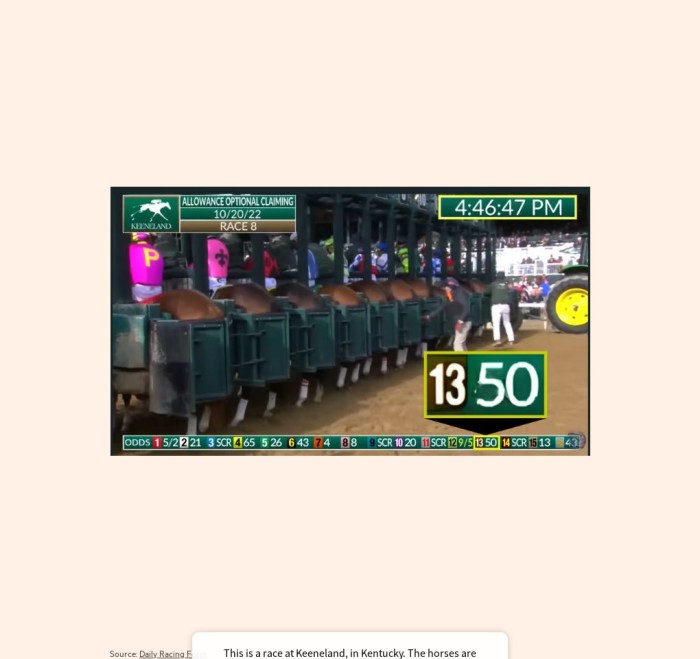

Because horses are data-generating creatures, the racegoers also pored over the small print in a thick periodical. Nearly everyone at a racetrack walks around clutching the reams of data in the Daily Racing Form newspaper or the track’s own programme. Each is jam-packed with figures that can, in theory, inform a day’s wagering.

But there are as many horse-betting strategies as there are potential bettors. One old-timer, who’d been coming to Gulfstream for 20 years, told me he knew all the local trainers and jockeys personally and, thus, who is hot and who is cold. A group of French-Canadian tourists said they favoured the most expensive horses. Another regular explained that he picked his horse because she was wagging her tail. “She’s ready to run,” he said, slapping his programme on his knee. Then he cut our conversation short to go place his bet.

McKeever, 57, favours a more empirical approach. He is tall and well-built, with the clean-cut carriage of an ageing college basketball star, and endlessly charming. He earned his nickname, “Pick Six”, for a type of bet in which you pick a track’s winners in six consecutive races — an exotic wager that can pay well into six figures. He’s hit hundreds of them in his life, including one in 2011 that paid out $1.1mn.

As he accompanied me around the Gulfstream grounds, McKeever hawked his artificially intelligent app, called EquinEdge, to the old-timers, the tourists, me and anyone else who would listen. His new venture is a recent arrival to an ancient sport now awash in AI-assisted technology.

Some $12bn was bet on horse races in the US in 2021, according to the Jockey Club, a thoroughbred industry group. Some of it came from people like me and the tourists, $2 at a time. Some came from people like McKeever, a few hundred a pop. And perhaps thousands per bet came from high-net-worth interlopers partying in the corporate box. But the most powerful figures in horse betting weren’t at Gulfstream with McKeever and me. They may not have even been in the country.

Collectively known as computer-assisted wagerers, or CAWs, they are largely anonymous. These sophisticated bettors use horseracing data to the extreme, employing algorithms, research staff and sweetheart deals to enrich themselves. In recent years, they have increased their capital and their wagering to unprecedented heights, accounting for as much as one-third of the money bet nationwide.

Horseracing in the US operates on a pari-mutuel system: all the money bet on a given race is put into a digital pool, the track takes a large cut (typically around 20 per cent) and the rest of the money is distributed to the winners. They’re playing against each other, not the house. A racetrack therefore is an enormous, faceless poker table. Bettors wager on horses, sure, but they’re really wagering that their opinion is better than everyone else’s. Lately the best opinions are coming from the machines.

I was raised on horse races at Prairie Meadows, outside Des Moines, Iowa, where I grew up. Despite its pastoral name, ecologically the place would be more accurately called Parking Lots. But it was the site of great childhood love and fascination. It was where I learnt the indelible smells of cigarettes and beer and paper currency. I often went with my grandfather, a cattle farmer and cardplayer. The racetrack grandstand, unlike the casino floor, was a place where he could both gamble and spend time with his small grandchildren. He’d lift me up so I could see over the counter at the betting window, and I’d hand over the notes he’d given me. “Two dollars to win on the No 4, please,” I’d whisper. Whatever I won, I could keep.

These were romantic trips but also analytical ones. Ever-present in the crook of my grandfather’s arm was the Daily Racing Form, the urtext of horseracing, with the data and the small print. There are, by my reckoning, a couple of thousand data points for an average race contained within. The pages list a horse’s name; owner, trainer and jockey; mother (dam) and father (sire); age; weight; sale price; dates and locations of all past races; times in those races at various points of call; relative position in the field at various points of call; the owner’s silk colours; a short qualitative note on each performance; and much else.

Grandpa taught me to read the Form, to turn its inscrutable figures into language, a dialect that could be understood and turned into a vision of the race that was about to be run. It was an exercise equal parts empirical and literary. At the track, I like to think, you are competing to tell the most compelling story.

The first horseplayer to popularise the modern empirics of the track was Andrew Beyer. The longtime horseracing columnist for the Washington Post, Beyer wrote a trilogy of classic texts on racing: Picking Winners (1975), The Winning Horseplayer (1983) and Beyer on Speed (1993). If the Daily Racing Form is horseracing scripture, these are the exegesis. It’s the last of these volumes that I remember most vividly, both for its evocative title and the dog-eared condition of the first copy I read, in my grandpa’s den.

The son of a professor, Beyer attended Harvard in the 1960s but never graduated. There were four racetracks near campus, and a final exam on Chaucer conflicted with the Belmont Stakes. In any case, he found that horse-race betting offered “more mental challenge and stimulation than any subject in the formal academic world”.

Beyer’s central hypothesis was that horses’ speed matters and can be quantified. It is a race, after all. The challenge was to create a metric to accurately gauge that speed. This is much easier said than done, and a stopwatch is not enough. Horses race on dirt of varying quality and depth and moisture, or on grass, or on artificial turf. They run many different distances, typically somewhere between five and twelve furlongs. (A furlong is an eighth of a mile.) They run through cold rain and hot sunshine. They run as members of small fields and large ones, rich fields and cheap ones. No two races are created equal.

In the early 1970s — armed with sharpened pencils, a mini calculator, large sheets of paper, tall stacks of the Daily Racing Form and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s — Beyer performed his painstaking work. By carefully and thoroughly accounting for the biases of tracks and adjusting horses’ clocked times accordingly, he collapsed the complications down into a single number: a speed figure. Speed figures allowed for reliable comparisons between California horses and Florida horses, between five furlongs and six, between a lowly claiming race and a big-money graded stakes. “Speed figures clarified mysteries, subtleties and apparent contradictions of the sport that I had always thought were beyond human understanding,” Beyer wrote in 1975.

By then, Beyer was already a successful gambler, in large part because his private calculations gave him a healthy edge. His books’ publication educated the market and eroded his advantage. Beyer accepted this trade-off because he wanted to be a published author. I sympathised. “In terms of mathematical sophistication, it was at best high school algebra,” Beyer told me of his arrival at the speed figure. “But it changed my life and, over time, it changed the game.” The approach became so ingrained that Beyer Speed Figures now appear in bold type in the Daily Racing Form, alongside every horse’s every race. The CAW syndicates, McKeever’s EquinEdge and many other recent projects are direct descendants of Beyer’s pencil-and-paper calculations.

In addition to their trenchant analyses, Beyer’s horse books pulsate with religious metaphor. He writes of the “gods who oversee horseracing”, “the discipline of a Calvinist”, “messianic fervour” and “winning streaks that make him think he is God”. The Daily Racing Form, he writes, “occupies the place in the existence of a horseplayer that a Bible does in the life of a fundamentalist”. I mentioned this theme to him and he seemed surprised. “I’m a very irreligious person,” Beyer said. He paused. “But when I discovered speed figures, they were the way, the truth, the light.”

Irreligious or not, there is a certain amount of faith to this game. Part of that is a physical fact. In person at Gulfstream, for example, the horses begin running out of a gate at the far end of the track, hidden, at first, by the tote board and an enormous video screen. They are back there somewhere, you know it, and it is by faith alone that they are running. Then they emerge and belief — and data — transform into muscular reality.

Beyer marvels at the CAWs’ sophistication and icy devotion to the science of the sport. He recalled meeting one player who had a university professor on a three-year retainer just to study the “distance factor” in horse races. With this sort of opponent, what chance does the public have? What chance does the student have of falling in love with the track? New horse bettors may just be happier betting on football these days, Beyer said. He created a monster, in other words. “The syndicates have contributed, in my view, to a total rip-off of the average player,” he said.

The most prolific of the computer syndicates are members of the Elite Turf Club, a company based in Curaçao, the island tax haven in the Dutch Caribbean. Only about 20 people in the world have active accounts with Elite. On a single day at Gulfstream Park last year, more than a quarter of the betting total — nearly $4.5mn — was placed electronically by Elite members. The club facilitates its mega-bettor members’ activities by connecting them at high speeds to various betting pools and by providing tailored reporting of their wagers and results.

The bulk of this Elite money is wagered from two accounts, called “Elite Turf Club 17” and “Elite Turf Club 2”. These two people alone, and whomever they employ, may account for nearly 20 per cent of all horse-race betting in the US, according to a Financial Times analysis of wagering data.

When I spoke with Scott Daruty, the president of Elite Turf Club, he told me that he wouldn’t answer any questions about wagering amounts or individual Elite members. “All of those are going to be met with a no-comment,” he said, citing confidentiality agreements. “Elite Turf Club is a wagering platform that services some of the largest bettors in the world,” he continued. “We’re servicing a limited number of customers, and it’s a bespoke, hands-on service that we provide.” The largest Elite accounts, the people who hold extreme power over the sport, guard their privacy closely; repeated attempts to arrange interviews with several of them were unsuccessful.

As it happens, Elite and Gulfstream Park are owned by the same company, the Stronach Group. Stronach owns a number of other racetracks across the US. (Frank Stronach, its founder, sketched the first plans for the gigantic Pegasus statue that greeted McKeever and me.) The computer syndicates are successful in large part because of deals they cut with tracks. These large bettors receive volume discounts known as rebates, and typically about 10 per cent of whatever they bet is returned to them to ensure their continued business. “We felt it important not to have a third party standing in between us and these customers,” Daruty told me, when I asked about the arrangement between Elite and the tracks.

“We wager lots of money, and on the other end of the spectrum is the general public,” David Bernsen told me. Bernsen is the manager of GWG Group, a collective of CAW players, specialising “in the development and management of high-capacity connectivity software and business solutions”, according to its website. There aren’t many major CAWs. Bernsen estimated there are four “very large” CAW bettors active in the US and perhaps half a dozen in a tier below them.

“The larger ones are sophisticated operations, like a stock-trading team,” Bernsen said. “They’re a proper business structure. You have your modelling side, your business side, you have your research and development side — a lot of money is spent.” He was quick to defend their role in the sport. “All we’re doing is balancing out the pool to make it more efficient. It’s not unlike flash trading in the stock markets or the crypto markets.”

This moneyed invasion into the sport of kings has goaded some people to devote their professional lives to investigating its impact. Patrick Cummings runs the Thoroughbred Idea Foundation, a think-tank founded in 2018 on the belief that horseracing was riddled with conflicts of interest and heading in the wrong direction. “These [CAW] entities bet big because that is what the math dictates. This is Wall Street meeting horseracing,” reads a report the foundation published in 2020. “They don’t lose, and if you try to reduce their rebates, they will turn to another source for betting.”

According to Cummings’s research, in the past two decades, adjusting for inflation, total betting on US horseracing from the general public decreased 63 per cent. Betting from CAWs, meanwhile, increased 150 per cent. Cummings called Gulfstream Park, the track I went to with McKeever, “ground zero” for the computer groups. “Horseracing is not in a position to reject customers. Yet we have accepted and embraced these whales, with little to no consideration of the damage that they do if left unchecked,” Cummings told me. “It’s not a good thing to be losing Joe Q Horseplayer, and we’ve lost a lot of them.”

McKeever, for his part, sees himself on Joe Q Horseplayer’s side. His team of 13 full-time employees and contractors at EquinEdge wanted to do its own CAW wagering. But McKeever refused. “I am for the small guy, that’s what I’m pushing for,” he told me. “I give them every bit of information that I have, everything we develop, all of our technology. Everything I do is for the little guy. The big guy thinks he knows it already. It’s the little guy I want to take care of.”

The Daily Racing Form, that august periodical in the crook of the racegoer’s arm, has itself entered the technological age. The publication is owned by Affinity Interactive, a Las Vegas-based company described on its website as “an omni-channel gaming industry leader with an expanded suite of casino and online gaming offerings”. The Racing Form offers a “Bloomberg terminal of racing” called Formulator and TimeformUS, which uses algorithmic prediction and data visualisation to aid handicappers. Marc Attenberg, the company’s senior vice-president for handicapping and data, was quick to note that there is still room for human reasoning and intuition. “There’s some shit going on that just doesn’t show up in the algorithm,” he told me. “That’s why people still love it. There’s still so much upside attached to coming up with those clever opinions.”

Attenberg reckoned that a computer betting by itself could break even at the track. But consistently making enormous profits requires the rebates the big CAWs have negotiated for with the tracks. (No one I spoke to, including the CAWs’ critics, suggested there was anything illegal about this arrangement.) The best players, he said, find ways to layer human expertise on top of the machine. “Racing thrusts you into these miniature dramas that you can turn into huge scores.”

I appreciated this description, and told Attenberg how I’d cut my teeth as a kid at Prairie Meadows. At one point during our conversation, I became frustrated with the modern state of empirical horse betting, missing bygone childhood evenings, telling tales about the race to come. “They’re goddamn animals running around in circles,” I said.

“There’s more to this than just a bunch of horses,” Attenberg said. “You handicap; you do the work; you watch the replays; you see the subtleties. You use the best possible tools and you leverage them.”

Detailed horse-betting data is hard to come by, but the annual reports of the California Horse Racing Board (CHRB) provide a good snapshot. For each track in the state, a major centre of the sport, the CHRB reports the total money handled from every registered location. These include the track itself, off-track betting facilities, websites, local betting parlours — and Elite Turf Club 17 and 2. According to these reports, over the past 15 years in California, members of Elite Turf Club have increased their wagering from 3 per cent to 30 per cent of all horse-betting dollars. A simple extrapolation from the California data suggests that Elite 17 and Elite 2 each wager on the order of $1bn a year on horses in the US.

“How did you get information about different Elite players in California?” Bernsen, the manager of the CAW collective, asked me, when I mentioned this. He sounded surprised. I also asked Bernsen for more detail on who was behind these mega-accounts. “I don’t discuss it with people,” he said. “Why is that important?”

Sophisticated, well-capitalised horseplayers aren’t brand new. A bettor named Bill Benter and his team made close to a billion dollars betting on horses in Hong Kong in the 1990s, and references to mysterious Australian whales occasionally punctuate the horseracing press. But their outsize prominence in the US is a relatively recent phenomenon. Bernsen attributed this in part to recent changes in the American tax code that made gambling more profitable.

While the exact strategies used by the current whales are closely guarded, like trading strategies at a quant firm, I spoke to some adjacent experts to get a sense of how they operate and how they bet. Chris Larmey, 62, is a horseplayer with a day job at a US national laboratory doing risk management and strategic planning. He has been involved with CAW teams, though he said he’s felt left behind by the “young guys” and their “black-box AI modelling”. Larmey started in the game as a maths major in university, manually entering race results on to punch cards and cadging time on the university’s mainframe computer to analyse them. This painstaking work equipped him to pick the first two runners at the 1982 Kentucky Derby, the 21-1 and 18-1 longshots Gato Del Sol and Laser Light. It was his senior-year project. He no longer remembers how much money he won.

Larmey described two broad strategies employed by CAWs. One is pure arbitrage. By closely monitoring the betting pools, one can sometimes spot naked inefficiencies — between the win and exacta pools, for example — and exploit them. The other is amassing gobs of data via existing databases and web-scraping, then analysing it to calculate a horse’s true odds and comparing that to its pari-mutuel price. For example, if a horse is expected to win 50 per cent of the time and it’s 2-1, that’s a great bet. If it’s 3-5, that’s a terrible bet. In other words, one wants to zig when the rest of the money zags. Price matters, and price is a reflection of the will of the people.

The CAWs’ machines bundle an attractive pile of bets together, sometimes thousands at a time, and ship them into the pool. “There are people that write the programs and babysit the computer systems, but it’s really automated wagering,” Larmey said. CAW players are also infamous for placing their bets at the last possible second, just before the horses dash out of the gate, to learn as much information as they can about the opinions of the general public and, therefore, the price of their bets. The technical ability to do this at speed and scale is what a group like Elite Turf Club offers its members. As a result, the public often swallows large, last-second odds changes as the big money comes flooding in.

“We’re just using an enormous amount of information, that’s what we do in the pari-mutuel business,” said Bernsen. “Construct our wagers and use technology to submit a large number of wagers as late as possible. That’s because we need the public’s input. The best predictor of the win pool is the general public — just wisdom of the crowds.”

CAWs have no quarter for the romantic notions of bygone childhood evenings at the track. “That’s one of the nice things about computers: they don’t have any emotions,” Larmey said. “You don’t have any of that regret or fear; it just executes according to the algorithms.”

I exchanged messages with a current computer player, one from the modern school, who agreed to talk anonymously. He was described to me by an industry insider as a “fucking genius guy”. He studied applied maths and finance and worked as a hedge fund quant. He learnt how to gamble by studying poker bots and “reading obscure machine-learning papers” and, to his credit, by spending time at the racetrack. He said he left Wall Street recently “to bet my personal capital full-time, split between horseracing and systematic trading of financial securities”. He’s not alone. Horseracing and the quantitative puzzles it presents are “really seductive for people who like that kind of thing,” Larmey said. “But it’s not marketed that way at all. Currently, in racing, it’s all about being hip and cool and going to the races in your fancy hat and your suit and making stupid bets.”

Still, if the general public consistently gets creamed at the track, they’ll stop coming to the track, and there’ll be no tracks. “It comes up a lot in our private conversations with racing organisations, horsemen’s groups, track operators, like, ‘What are you doing about this?’” Cummings, the think-tank director, said. There are levers the industry can pull to rein in the syndicates. Tracks can, and some have, cut off CAWs’ bets a few minutes before the beginning of the race, for example. Others have limited the size of CAW rebates.

There is another limit: the CAWs themselves. If they get too big, the sport will be just algorithms betting against algorithms. “Everybody realises we’ve got to have equilibrium here,” said Daruty, the Elite Turf Club president. “It’s got to be good for everyone to make sure this succeeds in the long run.”

McKeever gave me access to EquinEdge, and I fired it up one night in my apartment. I also deposited $100 on a betting site and pulled up a multicast of live races around the country. I intended to follow EquinEdge’s suggestions to make my wagers. I began in Charles Town, West Virginia, where a chestnut filly named Change The World led me to a trifecta. That was easy! I hopped north to Canterbury Park, in Minnesota, where a gelding called Ruby’s Red Devil won me an exacta. Back over in Charles Town, Full Moon Lover paid off handsomely at the top of my ticket. And just before the day’s racing was done, I sped down to Retama Park, in Texas, where Electric Cartel did the same.

I’d cashed four juicy tickets in a row and, within less than half an hour, doubled my money. I remained very quiet and still; it felt like I had discovered The Secret Truth. It felt like what I imagine an epiphanic religious experience feels like.

The next night was different. Longshot after longshot, none of them on my radar or the algorithm’s, pulled away down the stretch. At one point, I lost three consecutive races on photo finishes. My winnings evaporated and I went bust. God is dead.

It wouldn’t be the only time I’d faced a crisis of faith. A few days later, down in Florida at Gulfstream, my pockets were becoming lighter still. I wasn’t sure whether to blame the tech or my storytelling. McKeever and I took a break and sat down for a cheeseburger lunch. We were within sight of the parade ring, where the horses are exhibited before each race. I asked McKeever what he thought of the CAW players, the Goliaths to his customers’ Davids. “These big ones, they’re printing money, printing,” McKeever said. “But the CAW players aren’t going anywhere because they’re putting so much money into the pools. If it wasn’t for that, horseracing would be done. So how does the little guy have a chance? Well, he needs these algorithms. He needs the metrics to have a half a chance to win against these sophisticated systems.”

McKeever’s fascination with the game began much as mine had, as a young man at his local track, the now defunct Fairplex in Pomona, California. His friend worked for a famous horse trainer named Melvin Stute, who dominated Fairplex. McKeever bet an exacta on two Stute horses and won $200. “That was a crapload of money,” he told me. “I just remember feeling this overwhelming sensation, like excitement, like it was fun. I was kind of shy. I wasn’t as outgoing as I am now. And I just remember feeling a sensation and energy that I had never felt before.”

McKeever’s other professional life is running a company that supplies metals to the aerospace industry, but horseracing is what animates him. He eventually got a gig on camera at TVG, a horseracing network, in 2015. He is now an outspoken advocate and evangelist of the sport. He launched EquinEdge, which offers monthly subscriptions starting at $50 or day passes for $6, in 2018. McKeever is solidly in the teach-a-man-to-fish school. He teaches handicapping classes and hosts a horse-betting livestream each weekend, free to watch on YouTube. “I’m trying to teach you how to read a foreign language, essentially,” he said. And he doesn’t expect or want his acolytes to follow the AI blindly.

I spent a recent afternoon at McKeever’s penthouse condo in Fort Lauderdale during his broadcast. He broadcasts from a spare bedroom beneath a poster of the champion 1970s horse Secretariat. Between the racing, he fiddles with his algorithms and mixes in his own human wisdom. And to McKeever’s credit, he puts his money where his mouth is, placing real bets alongside his and his system’s picks. His viewers often follow along, a club of humans gathering around a machine-learning algorithm the way our ancestors gathered around a fire.

His viewers’ esprit de corps was contagious. A chorus of “BOOM” filled the chat whenever McKeever won a bet. The scene reminded me of burgeoning streaming-meets-education communities in chess, which is undergoing a remarkable boom of its own. “What EquinEdge is supposed to do is help people have a life,” McKeever said, “help them enjoy horseracing handicapping more and get new people to the game.”

This show, however, did not start well. Bet after bet came up short, the detailed empirical cases that had been made for them all for nought. After each loss, McKeever quickly deposited another $1,000 on a betting site and tried again. I worried that I was witnessing a meltdown. But at the very end of the day, a rich exacta came home. McKeever, and presumably many of his viewers, turned a small profit. McKeever, seemingly no worse for wear, took me to his favourite cigar bar where we had a few Scotches.

As we walked out, McKeever stopped and grabbed my arm. “I’m totally fucking crazy,” he said. “Do you think I’m crazy?” What ensued was a 20-minute conversation on a muggy Florida sidewalk, mostly consisting of McKeever worrying about the amount of time that EquinEdge took him away from his family, and what did I think of that, and would it work, and did I think he was crazy? I eventually assured him that I didn’t think he was crazy. Quixotic, perhaps.

I went back to Gulfstream alone the next day. It was raining, and a wet track makes handicapping even more difficult. Horseracing is a fickle game at the best of times. It was at this track that Beyer once punched a hole in a wall in anger following an unjust ruling that disqualified his favoured filly.

As I stared at the rain pelting puddles in the dirt, I imagined the CAW teams on their high-tech trading floors, staring at equine Bloomberg terminals, their algorithmic millions flowing into Gulfstream as the horses loaded into the gate. I sat down at a bar with cheap drinks and a view of the finish line. I closed the AI app, put away my phone and cracked open the Daily Racing Form. I took careful notes in the margins. I was trying to picture each race, to tell its story, to find the poetry on every page of the programme, as my grandfather had taught me.

An old man sat down next to me and gave me an enormous grin. “You really look like you know what you’re doing,” he said.

I apologised: “I’m afraid I have no idea.”

Oliver Roeder is the FT’s US senior data journalist. Sam Learner is a graphics journalist on the FT’s visual storytelling team

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first