“It’s incredibly weird for anybody who knows me that I’ve become the romance guy,” David Gaider tells me. “I’m the least romantic guy. Especially when I get to the characters saying ‘I love you’ to each other…” Gaider mimes the sickliness of the scene and his own horrified response. “Apparently I did it so well on Baldur’s Gate II that James Ohlen kept handing me this stuff. And, god, I hated it so much.”

It’s weird, in fact, that Gaider wound up working on Baldur’s Gate II at all – let alone that he became synonymous with Dragon Age and romanceable companions afterwards. At 27 years old, he ran a hotel in Edmonton, Alberta – the same city where, unbeknownst to him, Bioware was busy making its name. Once it came time to make a sequel to Baldur’s Gate, Bioware cast around for local writers, and a friend recommended Gaider, who had played D&D in the ‘80s before it fell out of fashion.

“I got this call out of the blue,” he says. “I went in for the interview and it was great. But it wasn’t very much money, so I turned them down. It seemed kind of sketchy. The office they had at the time had boxes everywhere and ductwork hanging out of the ceiling.”

When Gaider returned to work the following Monday, however, his boss had flown in from out east – as it turned out, the hotel had been sold, and Gaider was out of a job. He took the role at Bioware, falling into games just as he had the hospitality business. “I had no intention of doing this for a living,” he says. “It just kind of happened.”

But Gaider’s new career gathered speed quickly. Baldur’s Gate II’s lead designer, James Ohlen, loved the work he was producing and the rate he was producing it at. “They called me ‘The Machine’ back then, because I wrote so quickly,” Gaider says. “Baldur’s Gate II had 1.2 million words in total, and I think I ended up writing about half just on my own.”

The process reminded Gaider of being a tabletop dungeonmaster, “in that you were designing a story for someone where you don’t dictate their motivations necessarily. You’re leading them through the plot with little bits of cheese. It’s really the same with narrative design.”

The original Baldur’s Gate had numerous recruitable companions, but they seldom talked. Only in the sequel did your party members become complex individuals with gradually unfurling personal stories. They acted as your Greek chorus, or perhaps the angels and demons on your shoulders – reflecting on your actions and offering different perspectives on the central story. In other words, Baldur’s Gate II was where the highly influential Bioware model was first nailed down.

“James Ohlen came up with this idea of romances as something cool to try as a lark, not even thinking that they would be noticed much,” Gaider says. “I was just happy to be along for the ride. We had four romances and I did three of them, and that was really just Lukas Kristjanson and I sitting down, figuring out time-based conversation triggers so that your relationship grows.”

Bioware’s history since, in Dragon Age and the Mass Effect games, is testament to the fact that players responded positively and powerfully to the prospect of romanceable companions. They’ve become a crucial selling point of the western RPG genre, and heavily associated with Gaider in particular.

Thankfully, his initial hatred for romances subsided as he began to see them through the eyes of players. After writing on Knights Of The Old Republic, Gaider noticed that female fans were complaining about his handling of Carth Onasi, the romanceable space pilot with trust issues. “I went to a website that was specifically for female gamers, The Ladies Of Neverwinter,” he says. “And I asked, sort of polling, ‘What didn’t you like?’ I got a lot of really good answers.”

The deeper Gaider dug, the more invested he became in solving the challenge. “I became intensely interested,” he says. “How do I solve this Rubik’s Cube? What is it that you want out of a video game romance, specifically?” Ultimately, he wrote an unofficial denouement for fans looking for closure with Carth.

Ironically, it’s perhaps Gaider’s unromantic, analytical nature – ungiven to noisy gestures and forward overtures – that makes him such a strong writer of love stories. His new roleplaying musical, Stray Gods, features no fewer than four romanceable characters across its short runtime. And yet all of those relationships function as three-dimensional platonic bonds, too, should the player choose.

“Sometimes it can be a little bit too overt”, Gaider says. “I’m playing through Baldur’s Gate 3 right now. It’s great, but it also feels like the work I was doing ten years ago, when I just started plonking away at trying to write romances. I was making certain mistakes. It’s like, ‘Oh, this is very Romance for Games 101’, from my perspective. Not that I mean to put it down, it’s lovely and I’ve enjoyed it immensely. But that’s the feeling I got.”

For Gaider, writing good romances has been about making Carth Onasi-style missteps over and over, and then learning from them. “That’s how I got to where Stray Gods is,” he says. “Knowing what these romance arcs mean to these players, what they represent. Some of the things you can say when you’re writing them even though you don’t intend to, things that can leave a bad taste in someone’s mouth. You just avoid those.”

By working a romance from the angle of friendship, Gaider steers clear of serving characters on a platter. “There are some players who prefer the whole hog, as it were,” he says. “But I like a little more subtlety. The feeling that this is a character you’re dealing with that has agency of their own.”

Gaider has written beautifully in the past about ‘the gay thing’ – his position as an influential gay man in the industry. Every part of Stray Gods, from its writing to the visual design of its characters, is made with an awareness that there’s a queer audience who wants it. Yet in the early 00s, Gaider’s approach was utterly different. “When I started, I was gay but nobody at work knew I was,” he says. “I didn’t think of it as something that was connected to my work at all. I didn’t think it ever would be.”

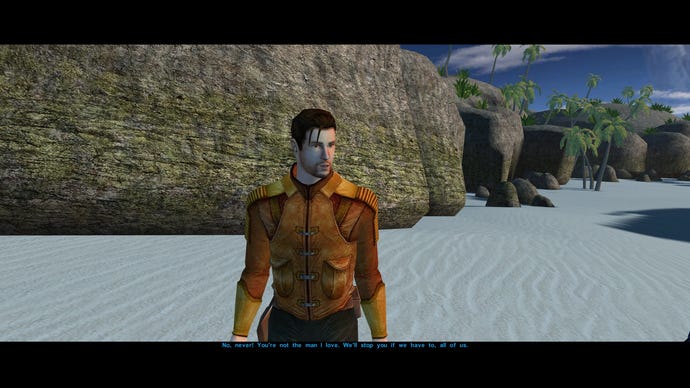

Bioware’s first gay character was Juhani, a feline Jedi with a romance storyline which Gaider neither suggested nor wrote. “It couldn’t be explicit, because LucasArts wouldn’t allow that,” he says. “So she couldn’t say ‘I love you’. It just had to be very gal pal. ‘These gal pals are really close!’ It had to be hidden.”

Gaider isn’t sure whether LucasArts were ever asked about the romance, or whether Bioware obfuscated it for fear of being overruled. “LucasArts certainly shut down anything they thought was over-the-top sexual innuendo,” he says. “But they looked at everything on a line-by-line basis, so if there was no single line that made it explicit, it went unnoticed.”

Bioware’s first openly expressed same-sex romance came in Jade Empire, and Gaider was bowled over. “When I heard that the other team had done this, I was like, ‘This is something we can do in a video game? Holy crap.’

« I had a character I wanted to make gay – Zevran, the assassin. And they were still going, ‘Oh, well, you know that’s a really small part of the audience, so if we’re going to do that much content for it let’s make him bisexual at least’. So he can do double duty.”

“It’s hard, especially for the younger audience today, to think of what it was like back then in the early 00s,” he adds. “Even when we started Dragon: Age Origins, on many levels, there was a lot of trepidation. I had a character I wanted to make gay – Zevran, the assassin. And they were still going, ‘Oh, well, you know that’s a really small part of the audience, so if we’re going to do that much content for it let’s make him bisexual at least’. So he can do double duty.”

Despite these concessions, Gaider’s mind was blown by the progress. He grew up in the 80s, when video games were considered toys for kids, and decision-makers at publishers were opting out of representation. That absence of queer relationships in mainstream art had a chilling effect. “I guess I always thought, ‘I’ll write fantasy romances, sure, but not for me. Nothing that I would ever play. I can write for other people, that’s cool.’ I never even thought that was a question that could be asked.”

By Dragon Age, Gaider had proven himself as a lead writer on the exquisite Neverwinter Nights expansion, Hordes Of The Underdark. Now he was trusted to flesh out Bioware’s plans for its own high fantasy world – Dungeons & Dragons with no licensing strings attached. “We liked working on Neverwinter Nights and Baldur’s Gate,” he says. “But having a third party as the IP owner was a constant battle at the time. Hasbro was such an ordeal to deal with.”

Gaider and a small team set about reinventing Baldur’s Gate, minus the D&D. “It had to be a Eurocentric fantasy,” he says. “The magic users had to be able to cast fireballs. Ray Muzyka was a big magic user in D&D.” In conversation with Ohlen, however, Gaider determined the elements they wanted to jettison, like the gods that wandered the Forgotten Realms as tangible beings with hitpoints. “There’s no atheism in that world because there’s no element of faith,” he says. “To me, faith requires doubt. That was one of my first questions: can we have a setting where there is no evidence of the divine?”

Dragon Age took off, and Gaider became the primary custodian of its world – leading the writing of all three released games in the series to date, as well as a stackful of novels and comics. “I felt like I’d gotten all the sword and sorcery stories out of me that I wanted to tell,” he says. Afterwards, he moved onto the early development of Anthem. “But that project was not going anywhere good,” he says. “I already could see the writing on the wall: ‘This is not gonna work out and I don’t belong on this team, but I left Dragon Age so there’s nowhere else for me to go.’”

The solution was to depart Bioware, Gaider’s home for 17 years. At the gym, he met another of the studio’s co-founders, Trent Oster – who by that time had set up Beamdog and put out the remasters of Baldur’s Gate and Icewind Dale. Gaider joined up as creative director, and helped pitch a pre-Larian version of Baldur’s Gate III to Wizards Of The Coast. “We didn’t really think we would get that,” he says. “But we took a shot at it.”

The project Gaider really wanted to make was a sequel to Planescape: Torment. “We flew down to Wizards Of The Coast and they loved it,” he says. The plan was to have events in 5th Edition Planescape coincide with those of the game – and to incorporate elements of Gaider’s story into the tabletop setting. “I came up with what I felt was a really strong story and a follow-up,” he says. “We’d done all the documentation and made all the characters, started the plots. We were ready to start writing. And then it fell apart. My impression was always that the funding just wasn’t there – Wizards Of The Coast wanted it to come from a third party.”

There was a sense that publishers might be wary of Planescape: Torment, which was a slow-burn cult success, and that a sequel might not sell. “I question that to this day,” Gaider says. “Planescape: Torment has this reputation as one of the best RPG games of all time. I think something coming out that built on it has a lot of potential to gain notice.”

Then again, that notice might not have been entirely positive. “When I think of it today, I wonder how well that would have gone over,” Gaider says. “Because the fans of Planescape: Torment are the most hardcore of the hardcore. Would they want their baby to be touched by the guy who did the romance stuff?”

Since his stint at Beamdog, Gaider has embraced indie life as creative director of Stray Gods at a brand new developer, Summerfall Studios. “If the company were for some reason to go belly up, well, it’s been worth it,” he says. “This is the most direct expression. I don’t have to work in the box that’s prescribed to me. I can make something that is meaningful. It’s the same reason I became the romance guy – it’s the challenge of it.”