John Barrett

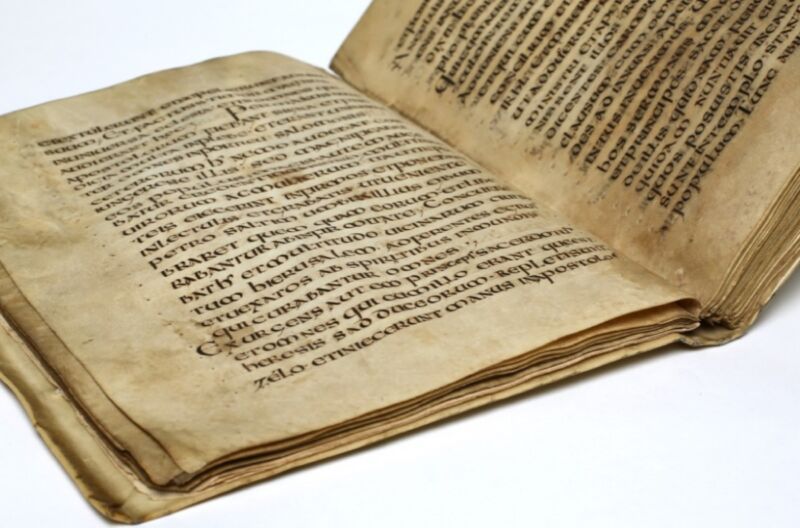

Jessica Hodgson, a graduate student at the University of Leicester, was poring over a medieval manuscript in the Bodleian Libraries‘ collection at the University of Oxford when she spotted a faint etched inscription on one of the pages. It seemed to spell out the name « Eadburg, » but the etching was too faint for full confirmation. So Hodgson turned to John Barrett, technical leader for a recent project at the Bodleian called ARCHiOx (Analyzing and Recording Cultural Heritage in Oxford), for help.

Thanks to the project’s prototype photometric stereo recording and 3D scanning systems, Barrett was able to confirm Hodgson’s discovery. The analysis also revealed multiple other etchings of the name « Eadburg » (in both full and abbreviated forms), along with several etched doodles in the margins. Who was Eadburg? Hodgson believes she was a highly educated woman of high status—possibly a female scribe or an abbess—who lived sometime in the early medieval period (between 700 and 750 CE). This latest discovery bolsters a 1935 discovery of the letters « EADB » and « +E+ » in the lower margin of another page in the same manuscript, both believed to be abbreviated forms of « Eadburh/Eadburg. »

The ARCHiOx Project

The ARCHiOx Project is a partnership between the Bodleian Libraries and the Factum Foundation, set up by Adam Lowe, an artist who trained at Oxford in the 1990s. In 2001, Lowe moved to Madrid to set up what he described to Ars as « a multidisciplinary workshop that’s really a playground for artists, where we build bridges between new technologies and traditional skills. » By 2009, there was so much interest from various historical projects regarding the group’s technologies that Lowe established the Factum Foundation for digital technology and preservation. Today it serves as a research hub for high-resolution, three-dimensional recording of the surfaces of objects housed in museums and institutions around the world—including tombs, paintings, and books and manuscripts like those housed at the Bodleian.

Various kinds of non-destructive X-ray imaging are frequently used by archaeologists and conservationists, among other applications. That includes multi-spectral imaging, which takes visible images in blue, green, and red and combines them with an infrared image and an X-ray image of an object. This can reveal minute hints of pigment, as well as hidden drawings or writings underneath various layers of paint or ink.

For instance, researchers have previously used the technique to reveal hidden text on four Dead Sea Scroll fragments previously believed to be blank. Swiss scientists used multispectral imaging to reconstruct photographic plates created by French physicist Gabriel Lippmann, who pioneered color photography and snagged the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physics for his efforts. And last year, scientists used the method to discover the first known Greek remnants of the astronomer Hipparchus’ lost star catalog, hidden beneath Christian texts on medieval parchment.

-

The Selene Photometric Scanner capturing one of the Lister copper printing plates in the Bodleian Library.

John Barrett -

18th century copper printing plates.

John Barrett -

Almost invisible when photographed conventionally, the fine etching on the reverse of Rawl. Copperplates g. 21 is revealed.

John Barrett -

Two 3D views of the recorded surface of Rawl. Copperplates e.65, generated using mapping software. The second example shows a layered view, using the albedo and a shaded render. The depth of each engraved line, measured at around 60 microns, can clearly be seen.

John Barrett -

18th-century copper printing plate with musical score engraved on back.

John Barrett -

The same plate with annotation revealing the actual notes.

John Barrett -

(left) A Ukiyoe woodblock print from Nipponica 373. (right) Albedo and shaded render.

John Barrett

New imaging techniques

Lowe knew of these methods, but he was surprised to learn that nobody was working on recording the surface of objects. « Traditionally, the digitization of books has [focused on] the extraction of the text, which can then be accessed online, » said Lowe. While he emphasizes that this is a very important activity, he thinks it has been done at the expense of the kind of work Barrett is doing at the Bodleian, looking at what he calls the « materiality » of those manuscripts: their surface qualities, book binding, typography, and the like. So the Factum Foundation started working first with 3D scanning systems, and then developed its own stereophotometric scanner, dubbed Selene, which the Bodleian is using for the first time.