[ad_1]

Search results

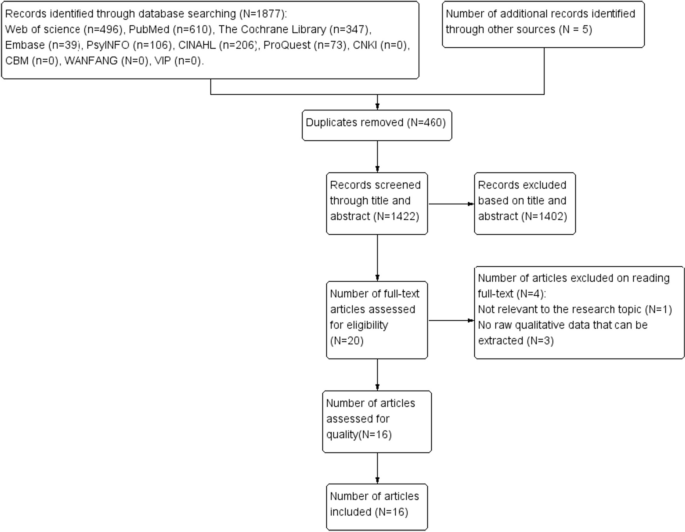

This systematic evaluation found 1877 articles in the initial search, and the researcher’s manual searching included five relevant studies. After reading the abstracts and titles, we removed 460 duplicates and 1402 studies that did not match the inclusion criteria. We reviewed all 20 of the remaining articles in their entirety and eliminated four of them: one paper with irrelevant research topics and three with unextracted primary qualitative data. Eventually, we included 16 articles. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram for study selection using PRISMA [36].

Study characteristics

The sixteen articles’ study characteristics were shown in Table 1. There were twelve qualitative studies and four mixed-method studies. Eleven studies used semi-structured interviews, three used open-ended statements, and two were conducted using focus groups. Fourteen articles used thematic analysis to refine the research, one used grounded theory, and one used inductive qualitative content analysis in the included literature. The mixed-method studies involved 488 participants, and the qualitative study involved 169 participants (we only extracted data from participants, excluding data from family members, medical staff, and service providers). Among the included studies, five studies focused on adolescents, one study focused on college students, and two studies focused on veterans. The age range of the participants was from 12 to 65 years. Seven studies mainly used smartphone apps for online interventions, three attempted to combine online interventions with offline professional help, and six used development web pages or online tools to deliver interventions. Seven regions were covered: Australia, the USA, the UK, Austria, Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

Methodological quality and dependability of studies

The content of the CASP is shown in Table 2.

Meta-synthesis

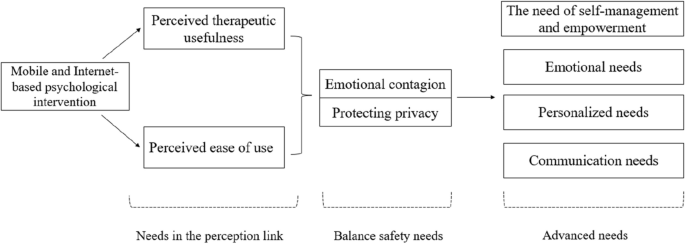

For a total of 149 results and 109 illustrations, the 16 qualifying investigations yielded 109 unequivocal findings (U) and 40 credible findings (C). The complete presentation of findings, illustrations, and the credibility assessment is available in Additional file 2. These results were consolidated into 14 categories and eventually distilled into three themes: needs in the perception link, balance safety needs, and advanced needs (See Additional files 3, 4, and 5 for more details). The thematic representation of research results is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Quality appraisal of synthesized findings

The results of the GRADE-CERQual of the Synthesized findings are shown in Additional file 6. This study summarized seven high-quality pieces of evidence, six moderate-quality pieces of evidence, and one low-quality piece of evidence.

Synthesized finding 1: needs in the perception link

The needs in the perception link represent the initial stage and one of the most critical factors in determining whether participants use mobile Internet psychological interventions. This includes perceived ease of use and perceived therapeutic usefulness.

Perceived ease of use

Technology with accessibility (Moderate confidence)

The category of ‘technology with accessibility’ was substantiated by four studies [20, 21, 37, 42]. Technical usability involves maintaining the normal usage of mobile psychological intervention software, encompassing tasks such as downloading, logging on, operating, and resource acquisition. Participants identified technical accessibility and availability as two major factors that hindered their use of the software or had a negative impact on their experience (findings 42 and 49). Furthermore, some software applications’ thresholds further diminished the accessibility of intervention, which is a key advantage of this mobile and internet-based psychological intervention (findings 23 and 127). Here are two examples of quotes:

The principal reason for lack of engagement with the application was a result of technical complaints (C).

Potential troubles in using technology are that having an app that needs a lot of time to load and apps that take a lot of storage place on the phone (C).

Suitability (Moderate confidence)

This category of suitability was supported by 12 studies [17, 20, 22,23,24,25, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45]. The suitability category reflected the multidimensional nature of participants’ needs for mobile and internet-based psychological intervention, encompassing how, what, who, where, and when they were used. Participants clearly expressed a preference for the use of the mobile and internet-based psychological intervention (findings 28, 88, 92, 133, and 146). The increased sense of connection and less pressure to seek assistance were the main effects of this enhanced accessibility (findings 58 and 123). Some adolescents noted that mobile and internet-based psychological intervention could facilitate their continuing care experience (findings 68 and 120). Here are three examples of quotes:

The accessibility and convenience of using smartphones to manage NSSI was another recognized asset (U).

This ease, accessible and simple of use was valued by participants as they did not want to add further stress to their situation (U).

The majority of adolescents believed that receiving a booster of intervention content through their smartphones would be useful for their continuity of care as well as an easy mode for information retrieval (U).

In terms of content accessed, participants expressed a desire for novel, easily accessible, specific, and feasible content related to self-injury and suicide-related behaviors through the app (findings 27, 62, 77, 84, and 101). Here is one example quote:

Respondents were consistently eager to learn new methods of reducing tension and explicitly wanted to know better ways of dealing with this than to incur self-injury (U).

When it came to the time and place of mobile and internet-based psychological intervention services, participants expressed a desire to be available in any state and all types of locations (findings 18, 15, 73, 81, and 146). However, application at times of crisis was crucial (findings 17, 33, 35, 73, 91, and 113). For example, when participants had intense suicidal ideation due to some triggers, they may press a button in the application and follow some simple interventions. At the same time, the software could directly send emergency notifications to specialist medical institutions for follow-up professional support. The followings are two example quotes:

while two other participants mentioned the environment as a possible limitation, as certain skills could not be used in public places (C).

Provide a way for safely and easily interacting, or connecting, with others, which was particularly helpful in periods of low mood or isolation when any form of interaction was difficult (U).

Participants in three studies indicated that mobile and internet-based psychological intervention should be integrated with specialist medical care (findings 16, 94, 136, and 139). The connection relationship ensured life safety for individuals currently experiencing severe suicidal ideation and during a period of emotional vulnerability. Participants also mentioned that the format of this online intervention was more suitable for adolescents, as they tended not to disclose their self-injury or suicidal ideation in their daily lives, opting instead to share them on their social media accounts (finding 106). The followings are two examples of quotes:

That BlueIce would be most effective if used in conjunction with professional support, particularly for those who may be experiencing more significant distress or more severe self-harm (U).

Automated monitoring has the potential to detect youth who reach out for help through digital media when their comments may otherwise go unnoticed (U).

Participants significantly recognized the need to tailor interventions for individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds (finding 59). For instance, several well-known Turkish idioms and metaphors were employed to articulate psychological distress and suicide-related behaviors in the context of mobile and internet-based psychological intervention. The cultural suitability of the online intervention contributed to Turkish immigrants feeling a greater sense of familiarity and connection. The following is an example of quote:

All participants spoke about feeling familiar with the culturally adapted content. They felt connected and were also able to relate to the intervention (i.e., cultural relevance) and often found it appropriate (i.e., culturally appropriate) (U).

Perceived therapeutic usefulness (High confidence)

Eleven research supported this aspect of perceived therapeutic usefulness [17, 20, 21, 23,24,25, 37, 40, 42, 44, 45]. On the other hand, Treatment needs were the most fundamental needs of people who had committed suicide-related behaviors and self-injury. Participants use mobile and internet-based services because their treatment needs could not be adequately satisfied in real life (findings 4, 6, 11, and 134). The primary reason given by participants for using online interventions was therapy. If participants could employ the intervention knowledge in their everyday life, it would be beneficial in lowering self-injury and suicide-related behaviors (findings 7, 14, 16, 22, 32, 48, 56, 75, 93, 99, 102, 140, 143, and 149). A proportion of participants were concerned that the online intervention would also not provide effective treatment (findings 37, 76, and 108). Interestingly, participants expressed a strong need for professional therapeutic support. They felt that online interventions needed to be deeply integrated with, rather than substituted for, professional therapeutic help, regardless of the circumstances (findings 38, 44, 95, and 132). The followings are four example quotes:

Further negative outcomes of engaging in NSSI involve receiving invalidating reactions from their surroundings (U).

Observing that intervention helps them or that they feel better after using it was the most prevalent reported motivation to engage with the intervention (U).

Adolescents were concerned about whether a machine could effectively interpret sarcasm related to suicidal communication and did not fully trust it (U).

This may suggest that self-harm requires more intensive support, meaning an app may not be sufficient. Participants felt that professional support was most appropriate (U).

Synthesized finding 2: balance safety needs

This theme focuses on two important contents using mobile and internet-based psychological intervention: emotional contagion and privacy protection. We needed to be careful to handle these two points in mobile psychological interventions.

Emotional contagion (high confidence)

Six research backed this area of emotional contagion [20, 22, 24, 37, 38, 45]. Participants of five studies reported that the constant attention and navigation to content about suicide-related behaviors and self-injury in the peer exchange community boards may have left them in a negative mood and exacerbated their illness (findings 10, 12, 20, 36, 63, 87, 97, and 117). Some online interventions used banning mention of keywords, such as suicide-related behaviors and self-injury, to avoid emotional contagion. Some participants expressed that the ban would limit their usual avenues of therapeutic expression and emotional release. Hence, participants need to balance emotional contagion with free expression (findings 119 and 145). Three typical quotes are shown below:

They were concerned that these questions about death and suicide might make individuals relapse or even make their condition worse (C).

Banning discussions about suicide could be challenging for people who need to talk about their suicidality (U).

Safety in online services for self-injury centered around the need for moderation (U).

Protecting privacy (Moderate confidence)

Nine research backed up this area of privacy protection [14, 20, 23, 25, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45]. Because mobile and internet-based psychological intervention might involve key privacy issues, participants were very concerned about privacy issues. They were very worried about how mobile and internet-based psychological intervention handled personal information and the negative consequences of privacy breaches (findings 24, 64, 72, 85, 107, 130, and 148). Participants appreciated the reliable privacy protection in several online interventions (findings 121 and 135). Adolescents, a sensitive group, mainly considered that treatment needs and privacy protection needed balance (findings 71 and 103). The followings are three examples of quotes:

There were concerns with how the information provided might be used, particularly that it might be used by clinicians to coerce the patient to make changes or force changes on the patient (C).

Participants expressed concern over confidentiality and the potential consequences for an individual in responding affirmatively to questions regarding suicidal thoughts, substance use and medication non-adherence (C).

Most adolescents believed there should be a balance between their need for protection and for free expression and privacy (C).

Synthesized finding 3: advanced need

This theme outlines the advanced needs of participants for mobile and web-based psychological interventions. It encompasses communication needs, emotional needs, personalized needs, and self-management and empowerment needs.

Communication needs (High confidence)

Seven research provided support for this group of communication needs [13, 20,21,22, 25, 39, 40]. Participants’ ideas were ambivalent about the impact of mobile and internet-based psychological interventions on communication needs. Some participants felt that the therapeutic intervention should be delivered face-to-face rather than through technological products (e.g., mobile phones, software, etc.). They felt that such a format would have a negative impact on the participant’s sickness and their capacity to communicate in real life (findings 25, 26, and 83). However, other participants indicated that online communication could help them to improve their communication skills and meet their need to share their experiences with people and professionals with similar experiences. Online communication could also help some participants who have barriers to communication in reality (findings 19, 90, 114, 116, 124, and 138). For example, some patients did not know how to communicate correctly with their doctor or were too embarrassed to express themselves during face-to-face interventions. They could learn the right communication skills through online interventions or express those difficult emotions through online communication. It is worth noting that, compared to others, adolescents showed a distinctly positive attitude towards online communication (findings 45 and 69). Here are three examples of quotes:

Some interviewees also expressed concerns about the functionality of the app and the potential difficulties in providing help in an interpersonal way (U).

Participants often expressed the wish to talk with other people (included therapists) through future NSSI apps to learn what is most helpful (U).

Adolescents also reported using their phone to text or call with friends, partners, therapists, pastors, or family for support with mental health or substance use issues (U).

Emotional needs (Moderate confidence)

Nine research backed up this area of emotional needs [17, 20,21,22,23, 37, 42, 44, 45]. The satisfaction of emotional needs was an essential part of being patients engaged in self-injury and suicide-related behaviors. Participants reported that the online intervention provided a non-judgmental, comfortable distance and safe emotional environment. The satisfaction of emotional needs was helpful in their treatment (findings 9, 43, 46, 54, 55, 100, 105, 110, 111, 118, 131, 141, and 144). Moreover, online interventions could help them communicate with patients going through the same experience, making them quickly gain acceptance and understanding (findings 115 and 142). The followings are two example quotes:

Participants also found it (watching videos on their smartphones or intentionally seeking company) helpful to be in therapy where they can talk without feeling judged or receive medications (C).

Young people identified a general desire for understanding and a specific desire to know others had a shared experience (U).

Personalized needs (High confidence)

Eleven studies supported this personalization category [14, 17, 20, 22, 24, 37,38,39,40,41, 45]. Personalization was a concern highlighted by almost all participants (findings 38, 40, 66, 74, 84, 89, 112, 122, and 141). Some studies explained why personalization was of such a concern to participants, mainly because of the distinct personalization of causes, experiences, and personal attitudes towards suicide-related behaviors and self-injury (findings 1, 2, 3, 5, and 96). The personalized content of the intervention enhances the freshness of participants and promotes ongoing engagement (findings 21, 55, 80, and 29). Two typical quotes are shown below:

Participants commonly referred to the importance of individuality with regards to how different types of self-harm require different support and how people cope in different ways (U).

personalised feedback did not only motivate them to continue but it also provided a safe environment to disclose their experiences (U).

The need for self-management and empowerment (High confidence)

Ten studies supported this category [17, 20, 21, 24, 25, 37, 39, 40, 43, 44]. Some participants indicated that a lack of motivation to improve was the main reason for their limited participation. Lack of self-management motivation results in low confidence and acceptance of online treatments (findings 13, 34, 39, 67, 78, 98, 125, and 129). Additionally, some participants also reported that the online psychological intervention helped them improve their psychological literacy, provided them with the ability to manage their own conditions, and enhanced their willingness to participate (findings 51, 57, 70, and 137). The followings are three samples:

There were times when they are open to receiving support to stop self-harming and other times when they were less willing to accept help and to stop the act of self-harm (U).

Almost all participants emphasized better self-management as one of the most important benefits of the online psychological intervention (U).

Some participants could see the benefit of using the app as an educational tool that improved mental health literacy, thereby facilitating improved communicate-on with mental health professionals and self-management of diseases (U).

[ad_2] ->Google Actualités