On the latest-but-one revision of their About page, Metacritic describe the process of calculating a videogame’s aggregate « Metascore » as a kind of « magic ». The FAQ cheekily invites you to « peek behind the curtain », evoking the figure of the theatre conjurer beckoning the audience on-stage to inspect the props, before performing the trick. You’re only shown so much, however. There are tables for conversions between different review scoring systems, demonstrating how a B- becomes 67/100, but the « weighting » Metacritic gives to each source publication when producing the combined Metascore is a closely-guarded mystery.

You could argue that the secrecy is necessary to avoid heavily weighted publications being targeted and pestered by fans to deliver positive reviews of forthcoming games, so as to swing the average (though in practice, Metascore soothsayers have long since sussed out which outlets have the most votes). But I think it’s better understood as a mixture of basic trademark protection and a mechanism of enchantment, a means of both deterring imitators and keeping avid readers guessing about the output. After all, no professional magician seriously wants to give away how the trick is performed, much as no meat magnate wants to show you the inside of a sausage factory.

Metacritic’s founders are former attorneys, and one way of analysing the « magic » of review scores and Metascores is through the lens of copyright law. Cornell professor James Grimmelmann digs into this in a – wait, come back! – genuinely very readable paper about whether scores and ratings can be copyrighted in the US, which you can download for free over thisaway. Combing a brace of court cases from the past century, Grimmelmann slowly puts together a picture of the product review score as a kind of shape-shifting, supernatural trinket – a strange, evolving compound of fact, opinion and « self-fulfilling prophecy ».

Scores can be defined as facts, he explains, in that they’re supposed to accurately describe the thing you’re rating, or at least, to accurately describe the raters’ feelings, perhaps using an established testing method that can be replicated by somebody else to produce the same result. They are opinions, of course, in that they represent one person or group’s interpretation of something that remains open to alternative judgements. And they are self-fulfilling prophecies in that they can determine how people respond to the thing being rated, shaping reality to fit their conclusions.

Picking one of these definitions is sort of like choosing a wizard subclass in a role-playing game: it offers up particular spells, different arcane verbs with which to operate upon the product and its consumers. « If ratings are facts, then they are discovered, » Grimmelmann comments. « The rater’s job is to investigate the world to learn the true facts about the subject. If ratings are opinions, then they are created; the rater’s job is to produce a personal evaluation of the subject. If ratings are self-fulfilling prophecies, then they are imposed; the rater’s job is to provide a vision so compelling it will be universally accepted. » In practice, Grimmelmann goes on, people tend to slide between these three understandings of a score, and you can see this in how commenters on videogame reviewers end up talking past one another as they debate whether scores are « objective » or « subjective », and so on. That slipperiness is maddening, but it also makes scoring an inexhaustible topic of discussion. Everybody pulls a different rabbit from the hat.

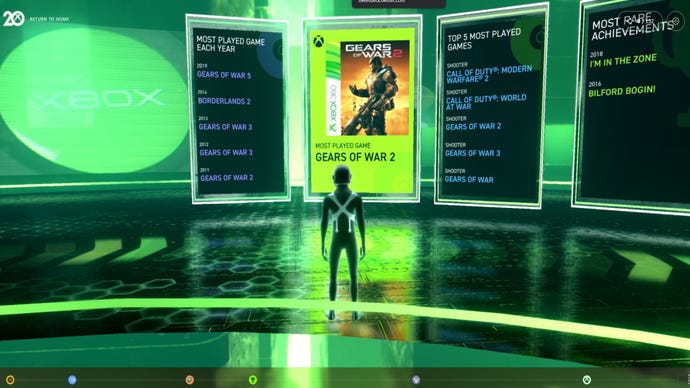

Scoring and grading stuff is a tradition that extends back to the dawn of capitalism, but videogames are, I think, uniquely score-able because they are so heavily defined as experiences by numbers and acts of quantification: level-ups and loot tiers, high score tables and virtual currencies, achievement lists and completion times or percentages, to name a few.

Developers rely on scores and ratings not just to model rewards but to render their worlds intelligible to players. They offer spaces in which, to collapse Grimmelmann’s first and third definitions, the numbers are a means of shaping reality because they are reality – they are both the systems you’re asked to manipulate, and the trinkets you get when you do so skilfully. This is especially true of today’s so-called « role-playing » games, which can be broadly interpreted as fantasies of how the very systems of gradations we use to value commodities may become commodities in turn. They exist, openly and ecstatically, as sprawling catalogues of objects to sort by power level, rarity and exchange value, and the process of « saving » their worlds is inextricable from the act of making those numbers go up.

It’s no wonder, then, that conversations about videogame scores and aggregate scores are so feverish: we’ve been taught by many of the games we play to regard scores as enchanted, world-saving artefacts. Metacritic’s editors appear cognizant of the parallel between scoring and videogame progression: on the latest, simplified version of their About page, the site invites visitors to « level up your experience » by leaving a reader review. But perhaps enchantment isn’t the only applicable RPG metaphor here. Perhaps it’s better to think about Metascores as a form of alchemy.

We call Metacritic an « aggregator » but you won’t find the verb « aggregate » on the site itself – after all, if « metamagic » were just about adding scores up, it would be harder to define as « proprietary ». On their older About page, Metacritic present themselves instead as « distilling » critical verdicts, so as to « capture the essence » of critical opinion, like a medieval potion-brewer attempting to refine a substance to its purest form.

As any reviewer could tell you, Metacritic’s « distilling » of critical voices very easily becomes distortion. One intrinsic failure is that the site’s editors treat every other numerical scoring system as a derivation of their own scale, so that a 4 out of 5 star rating is expanded into 80% on Metacritic, whereas in practice, these two grades conjure very different emotions, based on the ways they’ve been applied across media generally. Another problem is the practice of quoting a single paragraph or sentence from each review, which leads to misreadings and arguments based on a single phrase out of context.

Going beyond such blow-by-blow objections, the fundamental problem with Metacritic’s aim to « capture the essence » is that it presents disagreement as a form of impurity, and petrifies « the critical consensus » into a trophy that takes precedence over discussion, to the point that writing a review that’s out of step with the aggregate is viewed as deliberately « tanking » it – an act of vandalism deserving of mob justice. This has had an absolutely terrible effect on videogame criticism. Speaking as a reviewer, awarding what you suspect will be an « outlier » verdict feels like putting up a really shit Bat Signal for the grumpiest elements of the fandom. There’s always the temptation to either hedge your conclusions or defiantly lean into them, with the knowledge that you’re probably going to get dogpiled either way. There is a pervasive eeriness and self-alienation to the process of having a review featured by an aggregator, which you can read in well-trodden Marxist terms. Your words and opinions are ground up, mixed with those of many other reviewers, and alchemised into a blunt, shiny bauble which is then smashed over your head.

The ostensible light at the end of the tunnel here is Metacritic’s rival OpenCritic, launched in 2015, which doesn’t « weight » individual reviews the same way. But OpenCritic operates its own school of non-replicable « magic » born of smaller forms of opacity, such as what exactly distinguishes a « Top » from a rank-and-file reviewer when calculating the « Top Critic Average ». And it too « distils », conflating score systems and cherry-picking paragraphs, in order to devise its product.

It’s perennially hard to say how much Metacritic and other aggretators really affect the fortunes of game developers. Different games, types of game and studios have differing levels of exposure to aggregator culture, with canny or lucky developers building audiences outside the usual promotional channels. But it certainly has clout. The industry’s history is awash with anecdotes about teams being denied bonuses and missing out on gigs because their latest work fell short of that lush green 90. This is Grimmelmann’s idea of the score as a « self-fulfilling prophecy » in action: the aggregate is an oracle that decides what will sell and who is worth banking on. But Metacritic doesn’t just influence what gets made – it also helps decide what gets preserved. In 2008, Microsoft announced plans to delist a number of Xbox Live Arcade games based on their Metascores, as though paving over the fossil record at a certain level.

While it’s definitely a reach – I am very much not an economist and, I probably should have specified earlier, absolutely not a lawyer – all this makes me worry about the prospect of score aggregators doing for the games industry what US credit rating agencies did for the global stock market, back in the early 2000s. A credit ratings agency is another kind of scoring system – it gives the bonds issued by corporations or governments a grade so that investors can decide whether to buy them. In the 1930s, the US government prohibited banks from investing in bonds that didn’t get the right grades from the crediting rating agencies, effectively giving a small group of unelected professional opinion-havers the deciding vote over large swathes of the global finance industry.

In the 1970s, the US introduced a labelling system of « Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations » for credit rating agencies the government deemed trustworthy. But also during the 1970s, the biggest ratings agencies converted to a system whereby bond issuers pay for their bonds to be rated. This created a conflict of interest – rating agencies were motivated to give dodgy bonds good grades, in the hope of getting more work from those companies. That conflict led to extraordinarily risky lending opportunities being rubber-stamped by the agencies, which helped bring about the global financial crisis in 2008. TL;DR: the alchemy stopped working and the magic fell through.

I don’t think videogame review aggregators have nearly that level of influence, nor do I personally know of any instances of outright score-fiddling at places like Metacritic. But there’s a comparable relationship between review aggregators and the industry and field of gaming, and it isn’t hard to find precedents for how these playfully shrouded systems might be abused – a few weeks ago, Vulture unearthed evidence of third-party score manipulation at movie aggregator Rotten Tomatoes.

All this may read like the usual Metacritic teardown from a long-suffering games journalist, and I must admit I’m very relieved to now be writing for a site that doesn’t do scores at all (spoiler alert: an earlier draft of this essay was penned in the wilds of freelance). The thing is, even as a reviewer who is used to getting it in the neck from outraged Metascore-chasers, I enjoy the magic and alchemy of « metacriticism ». I, too, covet the lustre of a Metascore page that is solidly green, cleansed of yellow or red contaminants, much as I enjoy looking at a Destiny inventory’s worth of purple weapons. I also like aspects of the discussion around Metascores – it’s fun to dip into aggregator prediction threads and compare player speculations with my own, under-embargo opinion of a forthcoming game. And I think review aggregation can have genuine utility within the undead machinery of commodity consumption, if only as a way of saving labour. At their best and humblest, aggregators, like scoring systems themselves, offer simple shortcuts for people who don’t have the time or interest to read several pieces of criticism. They exist to give you a rough overall sense of the huge volume of criticism out there, while directing readers outward to individual critics.

Strip the aggregate verdict of that hypnotic enchantment, disclose in full the alchemy of its creation, and aggregation could have some kind of healthy community role – bringing publications and their readers together and putting everybody in conversation. Aggregate scores might serve as meaningful mechanisms of discovery by means of equivalence, guiding readers from the blockbusters everybody wants to read about to other, lesser-known and more adventurous games that have been placed in the same grade. All this is very pie-in-the-sky – it would require Metacritic and their competitors to sacrifice a critical component of the business. But given Metacritic’s on-going and seemingly inescapable dominance of videogame criticism, it would be nice if there were more to « Metacriticism » than sleight of hand.