According to one unofficial tracker created by video game artist Farhan Noor, there have been 8000 layoffs in 2024 so far, following an estimated 10,500 layoffs in 2023. The leaders of Microsoft, Embracer Group, Epic and other industry giants have made swingeing cuts to their workforces. While larger companies have inevitably seen the largest reductions, many smaller developers and publishers have also cut staff or even closed their doors. Circumstances vary by company, of course, but as regards the biggest publishers, there are some broad overlapping causes: reckless or, if you prefer, « overambitious » expansion and overhiring during the pandemic lockdown gaming boom; lower-than-hoped returns on new technologies and business models such as NFTs; and rising global interest rates, which have scared away potential investors.

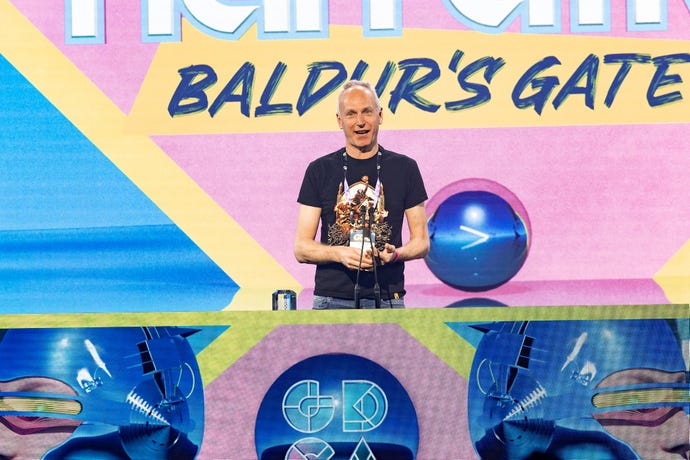

The carnage was uppermost in Larian CEO’s Swen Vincke’s mind when he accepted Baldur’s Gate 3’s Best Narrative gong at the GDC Awards last month. According to Vincke, the layoffs can be traced straightforwardly to a pattern of executive greed that sees company leadership betting the livelihoods and stability of their workers on whatever new idea seems capable of delivering instant growth for shareholders.

« I hear these [key performance indicators], because I spend a lot of time with these people, » Vincke told me after the show. « And I hear the craziest things. And the only way that you can reach those goals is by doing stupid things – you know, somebody finds a good game mechanic, and here we go, we’re gonna make 100,000 of them, right, and we’re just going to pump it up artificially until the players get sick and tired of it. And then oh shit, it doesn’t work any more. Let’s fire everybody. Oh, there’s a new one. Let’s do it again. Every single bloody time. »

Vincke’s point that industry layoffs are cyclical is worth stressing. Such has been the bodycount this and last year that it’s easy to think of the 2023-2024 reductions as an aberration, whereas they are aberrations only in terms of their scale. ‘Hire-and-fire’ is intrinsic to capitalism, but in Vincke’s analysis, many of today’s videogame executives are particularly guilty of repeated flights of short-termist thinking. Too often, he continued, publishers give serious thought only to the next financial quarter – « if you’re lucky, they think a year ahead » – and CEOs specifically are motivated by their quarterly bonuses to seek out quick-fix strategies for growth.

« You see it and you hear it and you know it when they’re telling you – you say look, two years from now, plenty of people are gonna get fired, » he went on. « This is what’s going to happen because of these choices that are being made right now, but [some people] will have their high bonuses, and that’s just a stupid system. I don’t think it’s a good system. »

‘How do we stop all this happening again?’ was a question I asked several developers and industry figures at GDC. I’ve come back with a cross-section of responses, many of which reiterate the importance of unionisation. « That’s a very sad reality of our current industry – the cyclical nature [of the layoffs], » International Game Developers Association president and Astral Interactive CEO Dr Jakin Vela told me, against the slightly confusing backdrop of a huge agriculture convention that had booked half the suites in the same hotel. « There’s no stability, and without stability, there’s a very disturbing lack of root chances for sustainability. »

Unionising isn’t a magic panacea – there’s not much any individual union can do about rising global interest rates, for example – but negotiating as a block will help workers temper the ambitions of management, and encourage leaders to think beyond the next quarter. « Will unionisation solve all of our problems? No, » Vela continued. « Can it support workers having a voice at the table? Absolutely. And so I think that’s sort of like the lowest hanging fruit in terms of what developers can do today. »

There’s been plenty of union advocacy in North America and Europe since the Game Workers Unite movement stormed GDC 2018. Unions have scored a few successes during the latest mass layoffs – this February, for example, the recently ratified Sega of America AEGIS union announced that they had negotiated the preservation of some roles and severance for departing temp workers during a round of cuts. According to a couple of union workers I spoke to at GDC, a big overarching ambition in North America especially is persuading employers that having a unionised workforce is better for business.

« A union doesn’t want to bankrupt the company – we want to keep our jobs, we want to keep working, we want sustainability in this industry, » Chrissy Fellmeth, international representative for the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, told me on the GDC show floor. There’s a « misconception » among employers that unions are just out to punish them, she said. « What we’re trying to do is work together – we’re not here to tear it down. We’re here to build it. We’re here to make our jobs and our lives sustainable for the long term. And with that is a love for our jobs in the company we’re working at. We’re not just here because we’re mad, we’re not here because we want revenge, we’re here because things can be better. And we want to work with employers to make that happen. »

One way in which unions can both incentivise employers not to take risks and lessen the potential fallout for workers is to haggle for more generous severance packages. Last year’s mass layoffs landed with differing degrees of severity: some developers were strictly speaking entitled to minimal compensation, for example, because they were on probation or classed as working on contract, but unions such as AEGIS have been able to negotiate more substantial deals, here and there.

« If the layoff has to happen in order to keep the company afloat, as opposed to lining stockholder pockets, then what can we do for workers that can secure their future? » Fellmeth went on. « It’s making sure that severance packages are fair, making sure that they have affordable health care plans that are extended past the date of the termination for a period of time, so that they can continue to have healthcare, making sure that the workers themselves can remain on their feet and stay in their homes and provide for their families in the instance that they have to suddenly be terminated from a job. »

« We’re interested in things like multi-employer healthcare plans, where regardless of which studio or employee you are working for, they pay into one collective plan, » IATSE communications director Jonas Loeb added. « And so if you get laid off and then jump to another job, you don’t have to change healthcare, all that paperwork that the company would be doing is no longer necessary. It helps a lot – it’s these little things that add up and let people focus on what’s really important to them, which is building the best games you can do. And you know, I think the business sometimes can step in the way of that. And, at the end of the day, the workers can point out problems on the shop floor and escalate those to management in a more effective way with a union than without one. »

While many developers I spoke to at GDC mentioned unionisation, others observed that there’s only so much a union can do to avert recurring mass layoffs because they’re always punching up. More top-down government regulation and oversight is needed to stop companies making disastrous bets in the first place. « Yes, regulation would support it, » Vela told me. « But I think that would be extremely challenging, because especially for such a global industry, there are already such disparate regulations and policies across countries. If we’re talking specifically for like the US market, I don’t know if the current dynamic is really supportive of that. »

Vela suggested that the current debate around « generative AI » tools in videogames could, however, be an opportunity to push for such government oversight and set a few precedents, because these technologies are a source of great suspicion among both players and developers. They’re heavily associated with creative theft, and there’s the on-going concern that automated tools will be a pretext for cutting jobs or rendering certain vocations obsolete. (If you’d like to know more, AI boffin Mike Cook recently wrote a four-part feature series on what « generative AI » is and isn’t, and what we can all do about it.)

« That is where a lot of developer fears are right now, especially concerning getting put out of a job, whether it’s writing, UI, art – there are serious and valid concerns about generative AI, » Vela went on. « So having protective measures to ensure that tools that these companies are using are ethical, that AI data is ethically sourced, that they add up to to enhancement and supplementation, rather than replacement… I think those kinds of regulations could be helpful.

« That may not necessarily support the cyclical [layoff] problem we have, but we have so many problems, » he added. « We have the cyclical problem. But we also have the new technology and fears of the implications of that new technology problem. And we have the harassment problem. I think to tackle the cyclical thing – for us, that might be the hardest at this point. But I think for most teams right now, it comes down to worker empowerment initiatives, whether that’s unionisation or whether that’s working with your current studio or management [in other ways], to figure out the best way for people to have a voice. »

The latest round of generative AI tools are certainly proving an interesting test space for union action. Microsoft recently came to a « first of its kind » agreement with ZeniMax union workers to give them consent over the usage of such tech in the workplace. Loeb suggested that people working in « animation, concept art and illustration, all of that stuff, are the folks who are the most afraid » of the introduction of generative AI tools. « And we need to be able to, again, have that ability to negotiate, and to have that consent over its use, so that we can create sustainability and longevity in our careers. » He argued, however, that focussing on the potential harms of generative AI tools might be counterproductive – what unions and employers need to do is thrash out a broader, enduring agreement about the introduction of ‘innovative’ technologies at large.

« There are other examples [of technology being misused] – workers being erroneously scanned into a game, right, which they didn’t sign up for because they’re not actors, as background characters or something. This is a privacy concern for people. What about the implementation of robotics in offices? There’s a lot of other technology. What we need to do is find a way to address new technology in general, in a way that is forward-looking, that isn’t only limited to whatever AI is today – it needs to cover a wide array of possible new technologies in the future. It’s a moving target. »

In general, Loeb feels there needs to be more collaboration between unions, and especially between workers rights advocates in different countries, to stop international companies simply shuffling their projects and resources around to avoid compromising with workers in any particular region. « We’re working with a lot of stakeholders internationally, in order to set standards across the board. It applies in one place and not another place, and things can move around, and that is just not a good option for anybody. It creates a precarious working environment for everybody. »

While evidence of this happening is sketchy, it’s possible that the scale of the industry’s layoffs last year will motivate more developers to seek out alternate forms of collective working. Take co-operatives, in which there is no traditional management hierarchy and no board of investors not-so-discreetly steering the ship. « Our structure is so unique, » Yannick Berthier of French worker’s co-operative Motion Twin told me during a showing of new roguelike Windblown. « It’s not like it’s better, but it’s different – really different. We are all partners, all sharing the pay, the vote, the decision, how long we work. Everything is really equal, or at least we want to turn towards that as much as possible. » There are few outfits like Motion Twin in the traditional games industry, which is indicative of the fact that getting such a framework going is hard work. Given the equality of status between employees, it boils down above all to working with people you can trust.

« Divesting » from the world of publicly traded companies doesn’t waterproof you against larger catastrophes, such as the economy going to shit. Motion Twin have had their « dark » spells and staff departures over the years, Berthier noted. « It’s not like we are an exemplar and everyone should be in a worker’s coop, or whatever. It’s super tough. » There are also practical challenges other companies don’t have to reckon with. « For example, we cannot keep money inside the company legally. [At the end of the year] we have to legally save some and the rest we have to share between the workers and but there is nothing left in the company, just small amounts so we can pay the bills mainly. That makes it super risky, because if you have a really, really bad year that’s finished, you don’t have a treasure chest where you save for the future. »

In general, Motion Twin don’t feel their experiences of running a worker’s co-operative qualify them give them special insight on the past year’s layoffs. But team members are proud that the studio has endured this long, and as with many indies, they regard the precarity of their situation as « the price we pay to be free, » in the words of another Motion Twinner, Thomas Vasseur. « We don’t have to convince any investors, because you cannot invest in our company, » he told me. « Legally speaking, you can, but it will be worthless because they won’t have votes, because we are bound to be controlled by the workers, no matter what. »

Perhaps the experience of 2023 and 2024 will spark the creation of more studios like Motion Twin. Perhaps it’ll drive a serious rise in union membership, too – a few unions have already been founded in explicit response to the 2023 mass layoffs, such as the Polish Gamedev Workers Union, which came together in the wake of reductions at Cyberpunk 2077 developers CD Projekt. In the short term, however, the people in the games industry with greatest ability to ensure the long-term livelihoods of workers remain the executives and their investors.

Vincke had more advice for fellow company leaders when I spoke to him at GDC – albeit, advice he doesn’t expect to be heeded. « It’s never going to happen, what I’m saying, but it should be about the love of the material, of the craft of what you’re doing, creating the feeling in players, which is really what most developers aspire to.

« And that’s so easily exploited, right? It so often gets exploited. There’s a lot of developers who are left brain only, not necessarily right brain – I don’t remember which one is the one that goes for profits! I’m not saying that it’s bad that companies to seek out profit, but you don’t necessarily have to sacrifice everything for its sake. Especially if you take a little bit of a longer term view. If you have a strategic view, don’t make those tactical mistakes, you’ll be all the better for it, and you’ll get better games and you’ll make even more profits. You just have to be a little patient. »